Janet Malcolm contributes the latest polemic against Richard Pevear and Linda Volokhonsky (hereafter P&V), the famed husband-and-wife translators of the Russian classics, whose preeminence in their field is now being challenged by a number of critics. I have read the previous arguments with interest (for instance, by Gary Saul Morson and Helen Andrews), but they failed to convince me that P&V grossly misrepresent their sources; in fact, most of these critics, including Malcolm, have a problem not with the couple’s command of Russian but of English. For my part, let me say at the outset that I do not read Russian—rather than hiding this important fact in a footnote to a misleadingly expert-sounding discourse about the nuances of Russian words, as Malcolm does.

Janet Malcolm contributes the latest polemic against Richard Pevear and Linda Volokhonsky (hereafter P&V), the famed husband-and-wife translators of the Russian classics, whose preeminence in their field is now being challenged by a number of critics. I have read the previous arguments with interest (for instance, by Gary Saul Morson and Helen Andrews), but they failed to convince me that P&V grossly misrepresent their sources; in fact, most of these critics, including Malcolm, have a problem not with the couple’s command of Russian but of English. For my part, let me say at the outset that I do not read Russian—rather than hiding this important fact in a footnote to a misleadingly expert-sounding discourse about the nuances of Russian words, as Malcolm does.

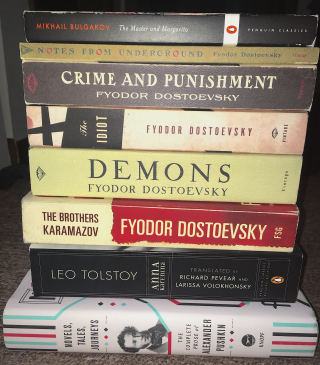

I feel slightly defensive on behalf of P&V, because they have been my main conduit to Russian literature, especially Dostoevsky. Kazuo Ishiguro once made the following observation:

I often think I’ve been greatly influenced by the translator, David Magarshack, who was the favourite translator of Russian writers in the 1970s. And often when people ask me who my big influences are, I feel I should say David Magarshack, because I think the rhythm of my own prose is very much like those Russian translations that I read. (qtd. by Rebecca L. Walkowitz)

I can say, similarly, that I have been influenced by P&V as much as by Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Chekhov, and Bulgakov. When I first tried, as a teenager, to read Anna Karenina and Crime and Punishment, I began with Constance Garnett’s versions and in both cases abandoned them around page 100. The fact is that I didn’t really start reading 19th-century English realist novels with any appreciation until I was in my 20s, and those are what Garnett’s translations tend to sound like, at least to ears untutored to Edwardian nuances. My introduction to literature came more through Shakespeare, the Romantic poets, and the modernists/post-modernists (Joyce, Hemingway, Faulkner, Morrison, DeLillo); so when I discovered P&V’s translations early in college, I was able to hear in their versions of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky the energy, the clarity, and even the bizarrerie of those non-Victorian writers.

Given that the Russians’ brand of realism comes out of European Romanticism and gives a spur to European and American modernism—striking the western literary imagination like a fiery boomerang in the same way that Latin American magical realism was to do a century later (I owe this analogy to Franco Moretti’s Atlas of the European Novel)—I see P&V’s calculated evasion of Victorian English as eminently appropriate. Without P&V, I doubt I would have sweated with Levin at the reaping or walked dizzily through the city with Raskolnikov during my college years’ long hot summers of extra-curricular reading, some of the best and most intense reading experiences of my life.

I am in sympathy with Malcolm’s desire to defend Constance Garnett from the disdain in which she is now held; she seems to be regarded patronizingly as a well-intentioned and high-minded English lady who got in over her head. Once I found my footing in literary history, I was able to appreciate Garnett more, and I read all of War and Peace in her translation (I particularly think she is good with Tolstoy, though I do prefer P&V for Dostoevsky). However, Malcolm strangely sets up the straw man of an entirely complimentary—a really very sweet—tribute to Garnett from D. H. Lawrence, which she reads as condescending, even though Lawrence would only intend to praise a writer by picturing her out in nature rather than locked up in a dusty study. By contrast, I would imagine that the roots of fashionable Garnett-hatred can be found in Nabokov’s Lectures on Russian Literature, which Malcolm does not mention. In any case, J. M. Coetzee’s defense of Kafka’s first translators, Willa and Edwin Muir, in his Stranger Shores, might be applied mutatis mutandis to Garnett:

The Muirs…introduced a difficult, even arcane German modernist to the English-speaking world years earlier than one might reasonably have expected this to happen. […] [Translator Mark] Harman would do well to recognize that, if a striving toward elegance—fluency is a better term—marks the Muir translation as of its time, then, in its very striving toward strangeness and denseness, his own work—welcome though it is today—may, as history moves on and tastes change, be pointed toward obsolescence too.

But Garnett’s English is now historical; it is for readers of Lawrence (and Eliot and Dickens)—who are not necessarily the budding reader’s first novelists these days, as they were not mine. And the budding reader is justified in choosing Tolstoy and Dostoevsky before the English novelists, because, frankly, the Russians are better and in some ways more relevant. (I imagine no 19th-century English novel speaks to American political realities in 2016 as clearly as does Dostoevsky’s Demons, for example.) Also, our 20th-century American writers’ swerve from Victorian realism led them to the Russians—Hemingway and Faulkner and O’Connor and perhaps most of the great Jewish- and African-American writers (for political as well as aesthetic reasons) clearly took more from the Russians than the English.

To see why the contemporary American reader might prefer P&V to Garnett, let me focus on one of Malcolm’s examples. She chooses a passage from Anna Karenina meant to indicate Dolly’s appearance as a selfless wife and mother, in contrast to the novel’s society belles.

Garnett:

Now she did not dress for her own sake, not for the sake of her own beauty, but simply so that as the mother of those exquisite creatures she might not spoil the general effect. And looking at herself for the last time in the mirror, she was satisfied with herself. She looked nice.

P&V:

Now she dressed not for herself, not for her own beauty, but so that, being the mother of these lovely things, she would not spoil the general impression. And taking a last look in the mirror, she remained satisfied with herself. She was pretty.

“Garnett’s ‘She looked nice’ is inspired,” Malcolm judges. And by the standards of Garnett’s English, in which “nice” evoked the fastidious and deliberate, it may be; in the contemporary American idiom, however, “nice” is a non-word, a way to say nothing inoffensively: “You look nice” is just what I would say to someone who didn’t look too good. “Pretty,” conversely, suggests an innocent form of the beautiful; it is without erotic connotation—you would say it of a child or a flower—and is therefore appropriate for this good woman trying to look well as she takes her children to church. For me, “pretty” is le mot juste. (Whether or not we approve of Tolstoy’s gender ideology is another question; the translator only needs to convey it vividly. But those of a feminist bent might find a critical foothold in P&V’s choice of “pretty” that is largely absent from “nice.”)

In these omni-politicized times, I always suspect people of lurking political motivations, so I wonder if Malcolm is not responding on some level to P&V’s politics; from Pevear’s prefaces, I have always gotten the idea that they were religious conservatives. Of previous inadequate translations of the opening sentence of Notes from Underground, Pevear writes, for example, “It speaks for the habit of substituting the psychological for the moral, of interpreting a spiritual condition as a kind of behavior, which has so bedeviled modernity.” In sympathy with Dostoevsky’s critique of the modern, P&V have tellingly avoided only the westernized liberal Turgenev among the canonical Russians. Garnett, in contrast, can at least be retrospectively cast as a progressive, a pioneering female literary intellectual translating the foreign avant-garde in the atmosphere of the New Woman.

An observation in conclusion: Malcolm quotes Pevear’s statement of ambition to use his translation to “enrich my language, the English language,” which she judges “bizarre.” But Pevear’s preference for using translation to revitalize one’s own language, or language as such, echoes (knowingly, I would think) the 20th century’s single most famous essay on the subject, Walter Benjamin’s “The Task of the Translator”:

Of necessity, therefore, the demand for literalness, whose justification is obvious but whose basis is deeply hidden, must be understood in a more cogent context. Fragments of a vessel that are to be glued together must match one another in the smallest details, although they need not be like one another. In the same way a translation, instead of imitating the sense of the original, must lovingly and in detail incorporate the original’s way of meaning, thus making both the original and the translation recognizable as fragments of a greater language, just as fragments are part of a vessel. For this very reason translation must in large measure refrain from wanting to communicate something, from rendering the sense, and in this the original is important to it only insofar as it has already relieved the translator and his translation of the effort of assembling and expressing what is to be conveyed.

“[T]he original’s way of meaning”: this is what I imagine I have gleaned, not only as a reader but also as a writer, from Pevear and Volokohonsky.

Thanks for writing up this defense of Pevear & Volokhonsky.

I’ve read their translation of The Brothers Karamazov. What they said of Dostoevsky, his rhythms, his humor, his voice – they fulfilled their promise, and what I got was a lively, powerful representation of the visionary Russian Christian author and his Shakespearean vision transmuted to the Russian social scene (a reading of George Steiner helped solidify my understanding of Dosotevsky’s Shakespearean dimension)

Thank you so much for defending Pevear and Volokhonsky. It seems after years of praise they’ve been getting non-stop hate and vitriol over the last 6 years from random critics even though their translations continue to sell and introduce new generations to Russian writing. Even Slavic scholars love and enjoy their translations of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. I don’t despise or dismiss Constance Garnett and what’s more, neither do P&V. Pevear in particular is very much a fan of Constance Garnett.

I still think their translation of Anna Karenina beats anything else out on the market today. That also includes the very good translations by Schwartz and Bartlett.

That said, their translation quality may vary with the writer as Russian writers have varying styles and they may not get everyone down given those writers difficulty. They are much stronger with Dostoevsky, Tolstoy and Chekhov than they are with Pasternak or Gogol. I can’t assess their translations of Leskov and Bulgakov. I hear they have just completed a translation of Pushkin’s complete prose which I can’t wait to read.

Thanks for your comment! I also look forward to their Pushkin translation; I’ve never read P&V’s versions of Gogol, Leskov, or Pasternak, but their Master and Margarita, published by Penguin Classics, worked very well for me.

This matter sounds like simple jealously. It reminds me of the quote: Academic politics are so vicious precisely because the stakes are so small.

Strange that I happened onto this site, but I was in an argument with some random redditor that called me a fool for liking the P&V translation of Demons and C&P…. I have no idea why, but they bought into the hype of Morson’s piece, which I was not familiar with at the time, and said I had bought into the hype of PV translation. I mean, LOL. I have no idea about hype, they were just the nicest looking versions at the store, and I knew I hated what I had read in high school.

I read Morson’s piece and various other pieces that all seemingly edged back to his criticism, and it honestly made an impression of inbred literary folk more than anything. Even in Morson’s comparison, I think I prefer the PV translation from Underground, which I have not actually read. Sure, I don’t prefer either of them in places, but Garnett is pretty “dry as shit” to quote the great Nabokov.

Anyway, John, you were a professor of mine at the U! You may or may not remember we traded some words once in digital form. Your class was great, too. Anyway, I have come to want to defend them as well. Maybe their translations are not the greatest thing ever, but the translations did get me back into these novels. I just absolutely could not get into the Garnett stuff, much like what I read above.

I found a more poetical sense in these translations, and for me at least, being a poet, it imbibed in me a care to keep reading. Going over various comparisons, I say translation is impossible to critique on an objective level unless it is absolutely terrible.

Anyway, I just happened over this piece without knowing the writer. Just wanted to say hi again! Good luck to you.

Hi Cole—thanks for getting in touch! I do remember you and our exchanges! Agreed on your sense on P&V’s more poetic quality. I think certain critics grew up with Garnett and others of her era (the Maudes for Tolstoy, e.g.) and experienced the 19th-century Russians as kind of Victorian novelists, which leads them to resent the modernity of P&V, especially their Dostoevsky.